IMPROPER RESEARCH PRACTICES

What are improper research practices and what are the consequences for Honours Thesis students who engage in them? Anything from inappropriately manipulating (Afudging@, Acooking@, discarding, or making up) data, to failing to acknowledge the use of another person=s data, or deliberately performing or not performing any action which would result in another investigator misinterpreting the results of your research. The University of Winnipeg Campus Guide lists various improper research/academic practices on Page 120.

The scientific community looks on this kind of misconduct with the same contempt and horror that society looks on spousal abuse or pedophilia: The consequences of being caught engaging in improper research practices or even of appearing to have engaged in them are extremely serious. Two famous examples concern a scientist whose suicide was probably attributable at least in part to accusations of misconduct which may not have even been his own http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Kammerer and a doctor sentenced to death by firing squad for falsely claiming he could locate bullets in the bodies of wounded soldiers. In 2004, the case of a famous ecologist hit the news. The next year it happened in Montreal.

It may seem excessive to rank improper research practices on a par with other terrible misdeeds and to penalize culprits so severely. A few examples of the consequences of this behaviour explain why it is so reprehensible. Imagine that you and your supervisor have decided your project will consist of testing a hypothesis based on the research of a previous investigator. As science commonly progresses in this way, it is a realistic scenario: Science advances by the extension and revision of the findings of those who have preceded us. Suppose, however, that neither of you know that the previous investigator faked his/her results, discarded data that did not support his/her hypothesis or committed some other type of misconduct. At some point you could find your research Arunning off the rails@ that is you might not get a procedure to work or your results could contradict those found previously by someone else. Your natural assumption would probably be that you made an error of some sort. This would probably lead you to repeat your efforts (if time permitted, which of course it might not). If you were comparing your results to those of someone with an established reputation or research published in a respected journal, you might conclude the contradiction resulted from your own inexperience or inadequacies. You would feel a deep sense of disappointment and frustration as you looked back on weeks or months of hard and apparently fruitless effort. This would be bad enough but it would Aonly@ involves your self-esteem and reputation. Think however about the broader impact of misconduct in the context of what you might be investigating. Suppose you were inspired to do research because a beloved parent, sibling or spouse had suffered or died of a terminal illness. Would someone else=s misconduct lead you and others to have wasted time and resources that delayed the discovery of a useful therapy? Would their misconduct lead to false hopes for numerous victims and their families? Could the misconduct lead to a procedure that made matters worse? The answers could be Ayes@ or Aquite possibly@. This then is why honest scientists insist that crushing punishments be applied to those guilty of improper or unethical research practices: Those who do so injure the very essence of how science operates and has achieved its successes.

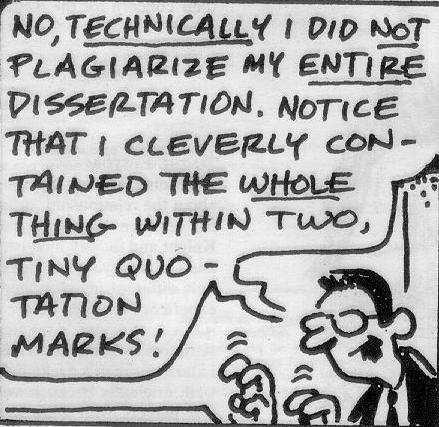

By trying to point out the disappointment and damage that misconduct can cause to fellow students, other researchers and even society as a whole, it would be nice to think no Honours Thesis student would be tempted to engage in improper research practices. That would probably not be realistic. So for those who may know better but decide this kind of behaviour has something to offer, a Acost-benefit analysis@ is worth thinking about. In other words what will happen if you get caught? These practices are a form of Academic Misconduct described as "Improper Research/Academic Practices@ in the University of Winnipeg Campus Guide (page 121, 7a.iii. As the Guide states, (Page 121), Penalties for Academic Misconduct can be severe and result in expulsion from the University. Please familiarize yourself with the information in Paragraph 7a.iii on Pages 120 & 121.

Often evidence of improper research practices is circumstantial and deniable. In such cases the student may not suffer the fate(s) listed in the Campus Guide but there will probably be unpleasant consequences nevertheless. It is almost a certainty that the supervisor and others who are aware of the matter will be reluctant or completely unwilling to provide the student with a good recommendation for a job, medical school, graduate studies, or anything else. This can be even worse than it appears because, once a student has done an Honours thesis, to be unable to offer a letter of reference from his or her supervisor immediately raises questions in the mind of whoever requires such letters. Another possibility is that the supervisor will be unwilling to publish results of research about which she or he has doubts. This means the student loses the valuable opportunity to list him or herself as the author of a scientific paper on their CV (Résumé). It may seem and is indeed unfair when anyone is penalized when the case against them is only circumstantial and deniable. The reality however is that once the bond of trust between the student and the supervisor is broken, consequences will follow.

What is the likelihood of being caught? The chances of being caught are higher than you might imagine. Your Supervisor and committee members are usually much more familiar with the research topic than you are. They are often able to recognize inconsistencies which you may not even realize are present. Your peers and the technical staff notice your activities in the lab. Even statistical analysis of your data can reveal data have (or may have) been tampered with. The case of Mendel=s renowned genetic experiments are controversial in this respect: http://www.is.wayne.edu/mnissani/PAGEPUB/Mendel.htm

It is a sad fact that unethical research practices take place more often than scientists would like to admit and more often than the public realizes (it is fairly certain that a few U. of W. thesis students have been involved in misconduct in the past). We have to ask why this happens given that it is so obviously wrong and risky. There are several possible explanations. Those which pertain especially to students are:

-The high stakes; there is great pressure to Asucceed@ (AI neeed an A+@).

-Misunderstanding how Asuccess@ is determined in research in general and in the Honours Thesis course in particular.

-Set-backs in the progress of the research. (The sample was harder to obtain than expected, data got lost, it took longer to process the samples than it was supposed to.

-Procrastination (laziness?) came into play and the time needed to do things properly ran out.

In addition to avoiding these risk factors, you should also avoid putting yourself in circumstances which invite suspicion:

-Don=t get so far behind in your research that you end up having to say, even if it is true, that you completed two or three months of work in one or two weeks and that you did it all between midnight and six AM when, unfortunately, there was no one around to observe and support your more or less unbelievable claim.

-Keep away from computers, labs, offices etc. which are not legitimately related to your project.

-If your research requires you to sign in and out of a building or lab on weekends or after hours, see that you do so; don=t put yourself at risk of having to say that you repeatedly or often forgot to sign in or out.

You can also protect yourself by:

-Keeping a lab journal and recording what you did, when you did it and the day-to-day details of your research. As well as protecting you from unjustified suspicion, a journal can be an aid if hind-sight leaves you in need of information which originally did not seem important enough to record.

-To the extent that it is practical, trying to do as much of your research as you can in the presence of your peers, staff, and faculty, so that at least people can confirm that you were going through the motions you were supposed to be going through.

Chronicle of Higher Education